The second of our seven University values that I would like to discuss in this Newsnote is compassion, following our acronym -- JCHIEFS.  It seems a rather obvious value within a health sciences complex -- one of the reasons we all go into health care in the first place. Yet, my experience suggests compassion is expressed in many different ways, for various reasons and with different outcomes.

It seems a rather obvious value within a health sciences complex -- one of the reasons we all go into health care in the first place. Yet, my experience suggests compassion is expressed in many different ways, for various reasons and with different outcomes.

Our culture today generally expects compassion to be an expression of a mature stable society, current political winds notwithstanding. This is an intellectual or extrinsic form of compassion -- culturally required that we express sympathy, even support, when something unfortunate happens to someone. In previous decades, we would rally around a family, or even a town or city, and provide whatever support was needed. Now we have institutionalized that support through insurance systems, FEMA, Red Cross, ADRA and other means. There is still an opportunity for individual involvement, but most of us just watch the news, shake our heads, and appreciate what others are doing.

But at an individual level, I am concerned about intrinsic compassion -- that virtue that arises from within, that moves our hearts and emotions. It comes from somewhere deep in our backgrounds or perhaps even our genes. The Good Samaritan sculpture on our campus is one of the best biblical examples of this form of compassion. So the question is: can we enable compassion, can we mentor and mold it, make it both realistic and effective? I think this is the challenge that Loma Linda must face as we seek to prepare the next generation of health care professionals.

Compassion is not just pity. It is not even sympathy or empathy, as important as those are in helping us identify with pain and suffering. Compassion includes a call to action -- to do something about a situation. It is the mandate that drives those of us in the healing professions to seek relief from suffering, search for cures, and initiate treatment protocols. But it must be tempered. Watching their first patient suffer and die is often unnerving for young nurses or medical students, as they want so much more from their relationship. We talk about the "wall" or "guard" that we watch develop, and even encourage, as we help students come to grips with pain and loss as a necessary part of becoming an effective professional.

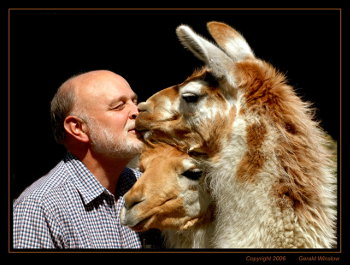

But how do we keep from becoming too jaded, too used to pain and death that it doesn't move us anymore? I was impressed last Friday as I watched a young veterinarian who had come to our house to "put down" our first llama, Hope, who had apparently suffered a stroke, and was clearly suffering from the effects of the aging process. My wife, Judy, and I had talked for weeks about whether it was "time." We finally concluded it was. As she prepared to begin, Judy went back to the house. Over the years she has taken this step too many times with our dogs.

But how do we keep from becoming too jaded, too used to pain and death that it doesn't move us anymore? I was impressed last Friday as I watched a young veterinarian who had come to our house to "put down" our first llama, Hope, who had apparently suffered a stroke, and was clearly suffering from the effects of the aging process. My wife, Judy, and I had talked for weeks about whether it was "time." We finally concluded it was. As she prepared to begin, Judy went back to the house. Over the years she has taken this step too many times with our dogs.

The vet gently patted Hope. The first injection, a sedative, was given. She and I watched Hope gradually wobble and lie down. Then the final injection to stop her heart was given as we silently waited. Though this vet did not know us or Hope, she showed genuine concern for this end-of-life moment. She gently murmured "she's gone" as she listened for the final heartbeat.

I am not making a case for euthanasia -- in people or animals -- though there is much discussion today on how best to humanely end a person's suffering. We have many more opportunities to express compassion during life than at the end. What do we do with the homeless man at the freeway off ramp? The Syrian refugees? Starving children in Africa? Or perhaps even closer ones, the disenfranchised gang member who can only find meaning in violence or drugs? The dysfunctional single mom trying to feed her children in San Bernardino? Answering these question is not for the faint-hearted! Many pull away, subconsciously knowing they either don't have an acceptable answer or are afraid to consider options.

These types of questions require us to look deeper at the causes of pain and suffering around us. Can we get at the roots -- the causes of these cycles of despair? Is there a Christian obligation — a moral imperative -- to do something? As I have said before in these Newsnotes, God doesn't expect us to have all the answers, but it seems He does expect us to be concerned, to care, to engage. It would seem that the act of engagement is more important than finding the solution. Certainly for the person involved, this is what matters.

So compassion made its way onto our list of core values -- an imperative for those of us with a commitment to serve, to help our fellow humans walking so fragilely on this earth. May it be embedded so deeply we never lose it and always seek for more effective ways to express our concern and support. And may it also distinguish LLU alumni, wherever they are, and in whatever circumstances they find themselves.

Sincerely yours,

Richard Hart, MD, DrPH

President

Loma Linda University Health