It was 1920 and Afghanistan was seeking help in bringing peace to warring factions. General Ghulam Mohammed Khan was part of a delegation sent to Mussoorie, India, to meet with British authorities. Located in northern India at an elevation of just over 6,000 feet, Mussoorie was a welcome retreat from the heat of India and a favorite of both the British and wealthy Indians, including Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter, Indira Gandhi, later leaders of the country. General Khan was a retired Afghan general who was now the minister of trade and commerce for Afghanistan.

The peace delegation met for some weeks, during which time General Khan fell sick. The account in the Adventist magazine Review and Herald does not indicate what disease he had, but he was referred to the Adventist sanitarium in Mussoorie, where he was treated. Apparently impressed with the facility, he returned each day and eventually invited W.K. Lake, the superintendent of the institution, to come and establish health work in Kabul. General Khan promised safe travel and reimbursement for Lake’s costs. Though the ruling “ameer” of Afghanistan was a young man at the time, General Khan assured Lake that the ameer listened to the advice of his counselors, and the Adventists would be welcome.

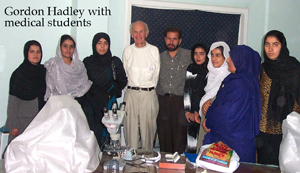

As far as we can tell, that call for help went unanswered for 42 years. Then, in 1962, Gordon Hadley from Loma Linda University was working on assignment for the World Health Organization (WHO) at Christian Medical College in Vellore, India. WHO officials had received a request from Afghanistan to help strengthen the medical schools in Jalalabad and Kabul, so they contacted Dr. Hadley to ask if he and his wife, Alphie, would travel to Afghanistan to evaluate this opportunity.

As far as we can tell, that call for help went unanswered for 42 years. Then, in 1962, Gordon Hadley from Loma Linda University was working on assignment for the World Health Organization (WHO) at Christian Medical College in Vellore, India. WHO officials had received a request from Afghanistan to help strengthen the medical schools in Jalalabad and Kabul, so they contacted Dr. Hadley to ask if he and his wife, Alphie, would travel to Afghanistan to evaluate this opportunity.

Thus began a growing love and respect for the people of Afghanistan by Gordon Hadley. From that contact, a plan emerged that eventually took several key Loma Linda faculty to Afghanistan to work with their medical schools during the 1960s. On one of those trips, Roy and Betty Jutzy tell of it being so cold in their hotel room in Kabul that the water in the toilet bowl was frozen in the morning. It was during those early years that the name of Loma Linda University—and Gordon Hadley in particular—came to be revered in the country.

By the early 1970s, Afghanistan had descended into a protracted and bloody civil war that destroyed much of its infrastructure and eventually led to the Russian occupation, followed by the mujahideen resistance, and then the Taliban coming to power. Much of Kabul was destroyed and Afghanistan became a “survival economy” where everyone took advantage of any opportunity for subsistence.

But the hope of improvement burned in many hearts, and in the late 1990s, the Taliban leaders started redeveloping the national infrastructure, including their medical schools. To do so, they turned to an institution that still held their respect—Loma Linda University. They contacted us, and subsequently a small delegation, including Joan Coggin, traveled to Kabul to evaluate what could be done.

Following that initial visit, the Taliban leaders sent a delegation to Loma Linda, including the young minister of higher education, to emphasize their commitment to medical education. I had the privilege of participating in those meetings as Loma Linda leadership struggled with a tough question—does an honest request for humanitarian assistance outweigh concerns about politics and security? We didn’t know as much about the Taliban then as we do now, but its hold on the country was complete, with strict Islamic law and no education for girls.

To its eternal credit, Loma Linda made the decision to place human need above politics and engage with the Taliban government. We laid plans to establish a small compound in Kabul that could house our faculty while they taught at Kabul Medical University. The challenges were enormous, including a lack of textbooks and functional labs, an inadequate and dispirited faculty, minimal administrative support, and large classes of male students who would do anything to get ahead and become a “doctor.” While there was a large medical school building built by the Russians, it had suffered sufficient war damage and had no running water, electricity, or heat. To support our office space and lab, we installed a small generator and water well in the nearby courtyard to provide minimal amenities.

To its eternal credit, Loma Linda made the decision to place human need above politics and engage with the Taliban government. We laid plans to establish a small compound in Kabul that could house our faculty while they taught at Kabul Medical University. The challenges were enormous, including a lack of textbooks and functional labs, an inadequate and dispirited faculty, minimal administrative support, and large classes of male students who would do anything to get ahead and become a “doctor.” While there was a large medical school building built by the Russians, it had suffered sufficient war damage and had no running water, electricity, or heat. To support our office space and lab, we installed a small generator and water well in the nearby courtyard to provide minimal amenities.

We were making small but steady progress in the medical school when the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center and Pentagon occurred in 2001. Fortunately Loma Linda had no one in the country on that fateful day, as Kabul soon felt the full wrath of the Afghan Northern Alliance and the U.S. military. For weeks, we didn’t know who had survived and whether our compound had been destroyed. But word finally got out that our duplex and house were still intact, so we made plans to return in early 2002. Everything had changed by then, with multinational security forces everywhere and a relaxation of the controlled environment of the Taliban. I will never forget standing on a street corner in Kabul on that first visit, hearing a school bell ring, a door swing open, and scores of kids stream out—boys and girls—with U.N. school bags, laughing and shouting as children should.

Shortly thereafter, local politics forced us out of our compound, and we had to reassess our future in Afghanistan. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) encouraged us to apply for a grant to manage the only orthopedic hospital in the country—Wazir Akbar Khan in Kabul. The next five years were filled with many challenges as we tried to bring better clinical skills and managerial techniques to the hospital, as well as continue our work with the medical school. A new apartment complex on the hospital compound was built for Loma Linda, providing a secure place for both long- and short-term staff. Jerry Daly managed the contract, while a series of alumni and others assisted in working at the hospital. Loma Linda’s reputation continued to be important as we worked our way through messy politics, bureaucratic impasses, a shortage of medicines and supplies, and many other hurdles. When the time finally came to turn the hospital over to the Afghan Ministry of Public Health, there was considerable sadness on both sides. Certainly the long legacy of Loma Linda in Afghanistan had been strengthened.

Sakena Yacoobi

In 1987-88, 25 years ago in Loma Linda, a young Afghan lady was sponsored by an American family to earn her MPH degree and chose to study at Loma Linda. I became acquainted with Sakena Yacoobi in the classroom. Bright and energetic, she was determined to make a difference back home, despite the civil war devastating her country at the time. On graduation day, in June 1988, Sakena invited Gordon and Alphie Hadley and my wife, Judy, and I to celebrate her accomplishment by sharing a traditional Afghan meal sitting on her bare apartment floor in Loma Linda.

Sakena was from Herat in the west of Afghanistan, but it was too dangerous to enter the country. So she started literacy programs for Afghan refugees in Peshawar, Pakistan, and other border cities. We heard from her occasionally as she continued pushing her dreams forward. Finally she went underground and reentered Afghanistan to start laying a foundation for the future. She established the Afghan Institute of Learning and started writing grants for expanding a system of private education. After 9/11, she could operate more freely in the country and established an office in Kabul.

During one of my visits to Kabul a few years ago, I decided to find Sakena. We finally got her phone number and established contact. She insisted on a visit, so we drove to her compound in a residential area of Kabul. It was great to talk again and see the impact she was already having in the country, particularly in education. As I was preparing to leave, she insisted I visit her School of Nursing. I agreed after she said it was located right there, in her compound. We walked out into the Afghan winter, with snow on the ground. Near the front gate, she turned to a shipping container with sheets of plastic hanging across the door. She pulled the plastic aside, and there inside sat 24 young Afghan women studying nursing in a shipping container with no heat and only a blackboard up front. With tears in my eyes, I vowed to never again complain about lack of resources.

Sakena sent me an e-mail some weeks ago. She planned to visit Loma Linda again and wanted to talk. We set a date and invited her to speak to our students that day. As she told her story in chapel, now in still-accented but much faster and animated English, the students were clearly moved and gave her a standing ovation. Sakena has been honored by many organizations for her vision and accomplishments, including our Doctor of Humanitarian Service in 2008. After chapel on her recent visit, we talked and her request was clear—help her start a new medical school at her hospital in Herat. Not sure what to do with that request! History tells us the challenge would be huge, but the Loma Linda legacy carries much hope in the hearts of that beleaguered country.